Support quality, independent, local journalism…that matters

From just £1 a month you can help fund our work – and use our website without adverts. Become a member today

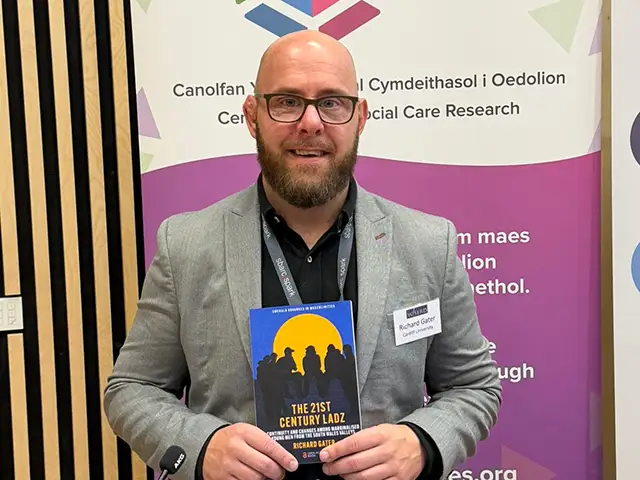

Dr Richard Gater walked into Abertridwr’s Oasis Coffee Shop, where I met him for this interview, wearing a Senghenydd RFC tracksuit top – not the stereotypical image of an academic, but one that gives an insight into his work.

His new book examines how young men in former industrial communities navigate masculinity, education and work – informed by his own journey from low-paid jobs to a Cardiff University PhD.

Growing up in Abertridwr, 46-year-old Dr Gater never imagined he would one day hold a doctorate and publish an academic book.

Leaving school without GCSEs, he spent years doing what he describes as a string of “dead-end jobs”.

His life began to change when, in his early thirties, he took a job as a park attendant and found himself connecting with local young people.

He said: “I got on well with them, and just thought maybe I could make an impact on their lives and prevent a trajectory similar to mine – while making my life better I guess – so I thought let’s go back to college.”

Encouraged by that experience, he enrolled on an access course in youth and community work at Ystrad Mynach College under the guidance of tutor Kerry Merchant – who Dr Gater described as “amazing”.

From there he went on to study sociology and criminology at the University of South Wales, graduating with first-class honours, followed by a master’s degree at Cardiff University.

In 2019, he began a PhD funded by the Economic and Social Research Council and supported by the Wales Institute of Social and Economic Research and Data – focusing on young men growing up in communities like the one he came from – drawing on an academic concept of ‘insider status’.

“Most people that do this kind of work have gone through school, through university, and then they’re coming back to look to a group of young men that are totally different to them – it’s an outsider status.

“Mine is an insider status,which for me, was hugely beneficial. I was very reluctant to use it at the start, but was encouraged to use it by my PhD supervisor.”

A study rooted in experience

Dr Gater’s PhD research has now been published as The 21st Century Ladz: Continuity and Changes Among Marginalised Young Men From the South Wales Valleys by Emerald Publishing.

The title is a nod to Learning to Labour, a landmark 1970s study by sociologist Paul Willis which explored the attitudes of working-class boys towards school and work.

His own study updates that research for the post-industrial era. It focuses on a group of young men in the South Wales Valleys – a generation growing up amid economic uncertainty, limited job opportunities and the lasting effects of deindustrialisation.

Through 120 hours of fieldwork and a series of interviews at a youth centre, he observed how the boys viewed education, employment and masculinity.

Pragmatic learners

One of the main findings of the study is that, unlike in the 1970s, these young men did not completely reject school. Instead, they developed what Dr Gater calls a “pragmatic approach” – engaging with subjects that seemed relevant to their future jobs, while dismissing others they viewed as pointless.

Rather than outright rebellion, this selective engagement shows a more nuanced relationship with education. But it also means that opportunities can remain narrow.

“Rather than a rejection of education,” Dr Gater explained, “they adopted what I call a pragmatic approach to education. So they selectively engage in topics that they thought were relevant to their future career, while rejecting those that they feel are not significant.”

“They knew that if they wanted to go to college, they knew they’d need English, Maths, Science. But then equally they knew that other subjects weren’t relevant, so they’d be truant from those days, and they were like, this information’s not relevant to me.”

Many of the boys he met had learning difficulties such as dyslexia, which made school even harder. Those barriers, he argues, were rarely recognised or supported, leading some to disengage altogether.

Rethinking work and manhood

While earlier generations of working-class men expected to find jobs in construction or manual labour, today’s young people see those options shrinking. Some of the boys Dr Gater met still aspired to those traditional roles, but others wanted to break the mould – aiming for careers in areas like media, catering or healthcare.

That shift, he says, reflects both economic change and a gradual evolution in masculine identity.

He explained: “A few of them, they had different inspirations – one wanted to be a paramedic, one wanted to do media, and one wanted to do cooking.

“And I guess the best example is the cooking – he was brought up in a single parent household, and his nan taught him to cook. It was that involvement that persuaded him to do something other than manual labour.

“I talk about a ‘rupture process’ … how that involvement with his nan ruptured those traditional ideas of what a man should do and work.”

Dr Gater argues that the old idea of the “tough, stoic” male is giving way to something more complex. In his book he describes how the boys expressed emotion and affection in ways that would once have been frowned upon – evidence, he believes, of masculinity adapting to new social norms.

“Two of the most prominent men in the book are right on the margins. They’re like smashing up shops, destroying everything – but they hugged each other.

“I was just like, how can two young men, who basically epitomise that toxic masculinity, hug each other?

“They got up and said, ‘We don’t do it the way you used to do it, we do it this way — come here broski,’ and they hugged each other.”

Communities still struggling

Despite signs of progress, his findings also highlight the enduring effects of deprivation. In communities where secure, well-paid work has all but disappeared, frustration can easily turn into anger or apathy.

Dr Gater believes that vacuum can still leave young men vulnerable to negative influences online, where simplistic messages about manhood and success – from the likes of Andrew Tate – fill the gap left by shrinking local opportunities.

“In this confusion people are filling that void – and my argument would be that we need to reverse that and fill it with hope and some interventions that fill that as well.”

He argues that the root causes are as much economic as they are cultural. With youth services facing funding cuts and traditional industries long gone, the sense of purpose once provided by work has been lost.

“The theoretical basis of this kind of working-class protest masculinity… it’s a form of masculinity born of deprivation. It’s developed in marginalised communities – where people have not got opportunities to education or employment. They develop this protest against society.”

Building hope and role models

Asked what could be done to change things, Dr Gater points to the need for better representation and opportunity. He believes young people need to see examples of success that look familiar to them – people from their own communities who have taken different paths.

That might mean more visible role models in schools, youth centres and the media who show that “being a Valleys man” doesn’t have to mean doing manual work.

He also calls for a rethink of educational pathways. Vocational courses that once offered routes out of poverty now often require GCSEs that many learners in deprived areas don’t have, effectively closing the door on them.

“I disengaged in my education and did the carpentry course and it didn’t require any GCSEs. But now that same carpentry course requires three GCSEs at A to C. So you can’t reject education anymore… there’s not many boys who are going to spend five years in college, who can’t afford to spend five years, trying to do a carpentry course.”

Looking back – and forward

Reflecting on his own journey, Dr Gater says it still feels surreal to have gone from labourer to lecturer. Having once been written off by the education system, he now teaches and researches at Cardiff University, with papers published in leading journals.

His book, he says, is both a study of working-class masculinity and a personal testament to the possibilities that open up when people are given a second chance.

“I look back and it just seems insane to be honest. I don’t quite understand how it got to this point with my own book launch. I’ve been published in two of the best journals in Britain – it’s just insane.

“For someone who didn’t read books till he was 33 and didn’t engage in school – it’s a bit mad, but I wouldn’t change my journey.”

The 21st Century Ladz: Continuity and Changes Among Marginalised Young Men From the South Wales Valleys published by Emerald Publishing and is available free to download online from emerald.com, with print copies also on sale through major booksellers.

Support quality, independent, local journalism…that matters

From just £1 a month you can help fund our work – and use our website without adverts.

Become a member today